Iraq’s election commission says the results of the first national vote since declaring victory over the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) group are expected within two days.

The vote on Saturday saw a record low turnout, with only 44 percent of eligible voters casting ballots. No election since 2003 has had a turnout below 60 percent. More than 10 million Iraqis voted.

Polling station officials blamed the low turnout on a combination of tight security measures, voter apathy and irregularities linked to a new electronic voting system.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi is running to keep his post. His chief rivals are political parties with closer ties to Iran, as well as influential scholar Muqtada al-Sadr, a staunch nationalist who campaigned against government corruption.

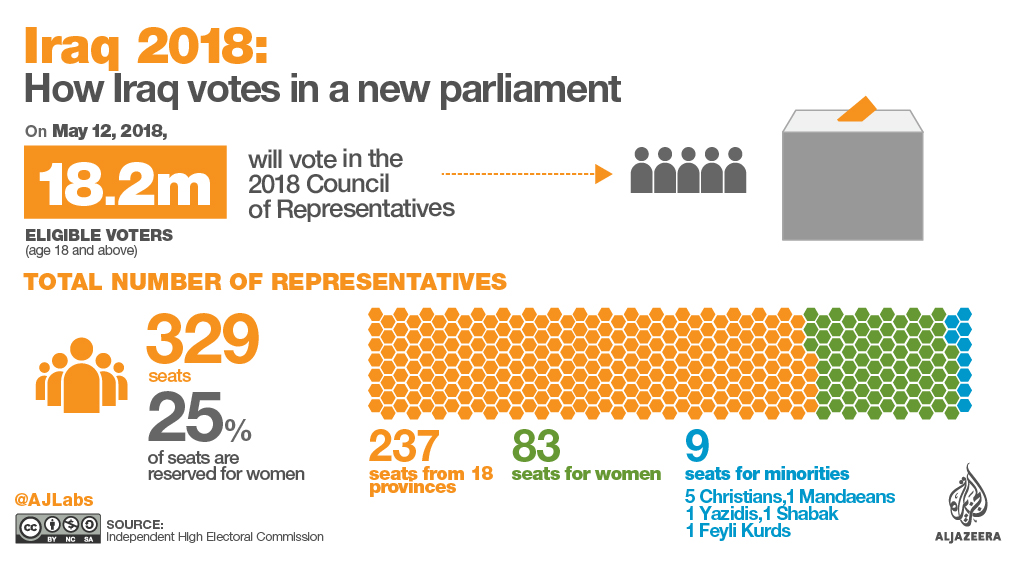

Nearly 7,000 candidates from dozens of political alliances are competing for 329 seats in parliament.

Al-Abadi, who heads the Nasr (Victory) coalition, is seen by some as a frontrunner, but he faces stiff competition from Hadi al-Amiri, a paramilitary commander heading the Fatah alliance.

Another strong contender is Nouri al-Maliki, a former prime minister who is seen as a possible kingmaker in the vote.

The results are expected within 48 hours of the vote, according to the independent body overseeing the process.

Difficulties in voting

By Saturday afternoon, less than 20 percent of residents in the capital, Baghdad, had turned out to vote, according to the Iraqi High Electoral Commission (IHEC).

Initial IHEC reports put the overall turnout at 32 percent, compared with about 60 percent in the last elections four years ago.

|

|

Commenting on the low voter turnout, Renad Mansour, a research fellow at UK-based think-tank Chatham House, told Al Jazeera: “Many Iraqis, especially in Sunni areas, do not view the election as legitimate. Many boycotted the vote because they do not believe it will make a difference.”

The low turnout was also partly blamed on a curfew and vehicle ban that came into force after midnight across several provinces in Iraq.

The restrictions left the streets of the capital, Baghdad, empty during the early hours of the vote.

With public transport also banned, only vehicles belonging to security forces and politicians were allowed to move around.

“The polling stations were far away from us and without cars allowed, it was really hard to get to the polling stations,” said Amal, a housewife living in central Baghdad.

The ban was partially lifted by al-Abadi later in the day, in an effort to improve turnout.

Meanwhile, only 285,000 people out of Iraq’s displaced population of two million had registered to vote, the electoral commission said.

| Security was tight at polling stations in Baghdad during Saturday’s vote [Wissm al-Okili/Reuters] |

The poll saw the implementation of a new electronic voting system for the first time in a bid to reduce electoral fraud.

Many wanting to cast their ballots at different polling stations across the country complained of irregularities.

“We visited IHEC and checked the biometric system, we were very surprised how faulty the workflow and management was, we reported this,” Hiwa Afandi, the head of the Kurdistan Regional Government’s department of information technology, said in a post on Twitter.

“Not using technology is better than a faulty implementation. Auditing and certifying is a must for such application where trust is a big issue,” he added.

The IHEC insisted that despite the irregularities, voting hours would not be extended because the electronic voting system had been scheduled to close at 6pm (15:00 GMT).

Iraq’s political system

Negotiations over the formation of a new government are expected to drag on as no single alliance is expected to able to win the 165 seats required for an outright majority.

Instead, the bloc that wins the most seats will have to rely on the support of smaller groups to achieve a majority.

Until a new prime minister is chosen, al-Abadi will remain in office and retain all his powers.

Political power in Iraq is traditionally divided along sectarian lines among the offices of prime minister, president and speaker of parliament.

Since the first elections following the 2003 US-led toppling of Saddam Hussein, the Shia majority has held the position of prime minister, while the Kurds have held the presidency and the Sunnis the post of speaker of parliament.

The constitution sets a quota for female representation, stating that no less than one-fourth of parliament members must be women.

|

Once the election results are ratified by Iraq’s Supreme Court, parliament is required to meet within 15 days.

Its eldest member will chair the first session, during which a speaker will be elected. Parliament must then elect a president by a two-thirds majority vote within 30 days of its first meeting.

The president is charged with naming a member of the largest bloc in parliament – the prime minister-designate – to form a cabinet within 30 days. If that individual fails, the president must nominate a new person for the post of prime minister.

In the past, forming a government has taken up to eight months. In 2005, allegations of vote-rigging delayed the ratification of election results for weeks.

Voting in Kurdish areas

Kurdish areas – where a banned referendum on secession was held last year – witnessed a relatively higher voter turnout compared with other parts of the country, according to reporters on the ground.

|

|

“In Kurdish areas, mobilisation might have worked in getting people out to vote. One of the main reasons behind this is that the referendum made Kurds realise that they cannot ignore Baghdad because when they did during the referendum, it backfired,” explained Mansour.

Following the September 2017 referendum, the Iraqi military seized control of disputed territories, including the city of Kirkuk.

The territorial losses left many Kurds disillusioned with their leaders.

As a result, the two main parties that have traditionally dominated the Kurdish political scene – the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) – are now expected to see a drop in their share of the vote.

In contrast, smaller political forces such as Goran (Change), the Democracy and Justice Party – led by former senior PUK official Barham Saleh – and the Kurdistan Islamic Group – also known as Komal, led by Ali Bapir – are likely to record a strong poll showing.

ISIL, US-Iran ties

In Baghdad, some Sunni voters expressed hope the election would help Iraq move beyond sectarian politics and become more inclusive.

“I voted for new people to come into the government,” Haitham Hasballah, from the Baghdad neighbourhood of Mansouria, told Al Jazeera.

“The political situation in Iraq has been getting from bad to worse, so we definitely need new faces.”

Another voter, Shaker Mahmoud, told Al Jazeera: “I voted for new people. I don’t want anyone from the old government. I’m hopeful that change will take Iraq towards a positive direction.”

Still, others in central Baghdad said they voted for al-Abadi, giving him credit for Iraq’s military victory over ISIL.

After ISIL overran nearly a third of Iraq in the summer of 2014, the group launched waves of suicide bombings targeting civilians in Baghdad and other government-controlled areas.

But, with support from a US-led coalition and Iran, al-Abadi oversaw a fierce war against the group’s fighters and declared victory over ISIL in December 2017.

Despite al-Abadi’s military achievements, Iraq continues to struggle with an economic downturn sparked in part by a drop in global oil prices, entrenched corruption and years of political gridlock.

The war left more than two million Iraqis, mostly Sunnis, displaced from their homes, with cities, towns and villages suffering heavy destruction. Repairing infrastructure across Anbar and Nineveh provinces, both majority Sunni areas, will cost tens of billions of dollars.

The election comes at a critical juncture in Iraq’s relations with Iran and the US.

Both countries are allies of the Iraqi government, but their bilateral ties are increasingly strained.

Source: Aljazeera